Market Court - Décision n° 2022/5760 du 7 septembre 2022 concernant IAB EUROPE

Hof van beroep

Brussel

Sectie Marktenhof

19de kamer A

Kamer voor marktzaken

Arrest

CONCERNING:

IAB EUROPE, registered in the Crossroads Bank for Enterprises under the number 0812.047.277, having its registered office at Place Robert Schuman 11, 1040 Brussels;

Appellant, original respondent;

assisted and represented by Kristof Van Quathem (kvanquathem@cov.com), lawyer with offices at Boulevard du Manhattan 21, 1210 Brussels and Frank Judo (f.iudo@liedekerke.com) and Peter Craddock (craddock@khlauw.com), lawyers with offices at Boulevard de l’Empereur 3, 1000 Brussels

AGAINST:

The DATA PROTECTION AUTHORITY, registered in the Crossroads Bank for Enterprises under number 0694.679.950, with its registered office at 1000 Brussels, rue du Mail 35;

Original administrative authority, hereinafter referred to as the ’Data Protection Authority’ or ’DPA’. GBA" or Dispute Chamber;

assisted and represented by masters Joos Roets ([REDACTED]) and Timothy Roes, lawyers with offices at Oostenstraat 38 box 201, 2018 Antwerp.

IN THE PRESENCE OF:

1. Dr. JEF AUSLOOS, domiciled at [REDACTED].

2. Mr PIERRE DEWITTE, residing at [REDACTED].

3. Dr JOHNNY RYAN, residing at [REDACTED].

4. FUNDACJA PANOPTYKON, a foundation under Polish law, having its registered office at ul. Orzechowska 4/4, 02-068 Warsaw, Poland with company number 0000327613, acting as representative of Ms Katarzyna Szymielewicz, residing at [REDACTED] in accordance with Article 80(1) of the General Data Protection Regulation,

5. STICHTING BITS OF FREEDOM, foundation under Dutch law, with registered office at Prinseneiland 97hs, 1013 LN Amsterdam, the Netherlands and KvK number 34121286.

6. LIGUE DES DROIT HUMAINS ASBL, having its registered office at Kogelstraat 22, 1000 Brussels, with enterprise number 0410.105.805, RPR Brussels.

Retaining voluntary intervening parties, hereinafter referred to as ? assisted and represented by masters Frederic Debussere (frederic.debussere@timelex.eu) and Ruben Roex (ruben.roex@timelex.eu), lawyers with offices at Joseph Stevensstraat 7, 1000 Brussels.

Having regard to the procedural documents:

- the decision of 2 February 2022 of the GBA (’the Contested Decision’),

- the petition of 4 March 2022, by which IAB Europe appeals against the decision No 21/2022 of the Dispute Resolution Chamber of 2 February 2022, in the file with file number DOS-2019- 01377, as notified by email and registered post dated 2 February 2022 to IAB Europe;

- the petition for intervention of the guardian voluntarily (Ausloos et al;)

- the preliminary hearing of 16 March 2022 of the Market Court, with a view to drawing up a calendar of conclusions for the debate on interim measures and the debate on the merits;

- The waiver of IAB Europe’s claim to the debate on interim measures;

- the parties’ summary conclusions;

- the bundles filed by the parties;

Heard the parties’ lawyers at the public hearing on 29 June 2022 and having regard to the documents they submitted, the case was taken under consideration for judgment on 14 September 2022.

I. Facts and procedural precedents

The different parties give their own factual account.

The Market Court is only reviewing a fairly brief account of the facts. In the further assessment, account will of course be taken of the facts as a whole and the documents filed by the parties.

Since 2019, the GBA has received certain (9 being 4 in Belgium and 5 foreign) complaints directed against Interactive Advertising Bureau Europe (IAB Europe). The complaints related to the compliance of the so-called Transparency & Consent Framework (TCF) with the AVG.

The TCF, developed by IAB Europe, aims to help ensure compliance with the AVG by organisations that rely on the OpenRTB protocol.

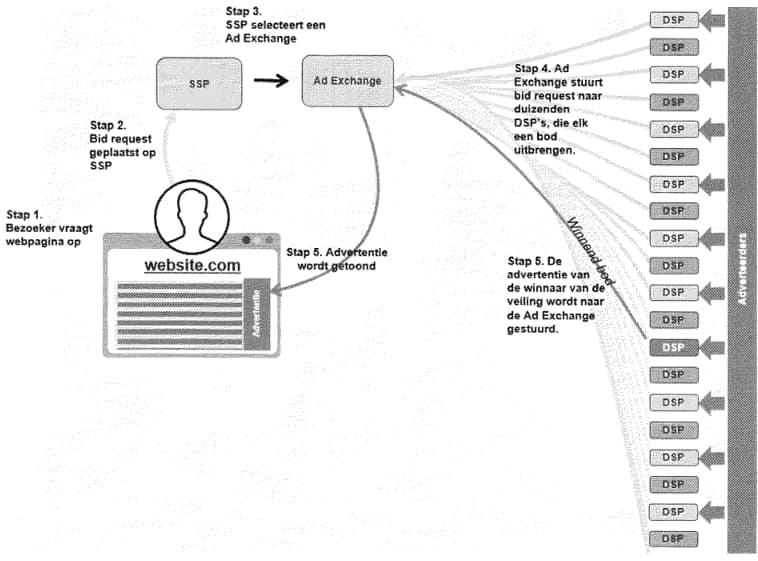

The OpenRTB protocol is one of the most widely used protocols for "Real Time Bidding", i.e. the instantaneous, automated online auction of user profiles for selling and buying advertising space on the Internet.

When users visit a website or application that contains advertising space, technology companies representing thousands of advertisers can bid for that advertising space in real time behind the scenes through an automated auction system that uses algorithms to display targeted ads specific to that person’s profile. When users first visit a website or application, an interface (a Consent Management platform or CMP) appears where they can give their consent to the collection and sharing of their personal data, or object to various types of processing based on the legitimate interests of adtech vendors.

This is where the TCF comes in (parties disagree on whether the TCF is a system or a standard and the Market Court will continue to refer to it as a ’standard’): the TCF facilitates the capture, via the CMP, of user preferences. These preferences are then encoded and stored in a ’TC string’, which is shared with the organisations participating in the OpenRTB system, so that they know what the user has consented to or objected to. The CMP also places a cookie (euconsent-v2) on the user’s device. In combination, the TC string and the euconsent-v2 cookie can be linked to the user’s IP address.

The TCF plays a role in the architecture of the OpenRTB system, as it reflects user preferences regarding vendors and various processing purposes, including the provision of customised advertisements.

The "system" can be schematically represented as follows. This picture is therefore purely illustrative and does not bind any of the parties involved:

The GBA Inspectorate will issue an investigation report on 13 October 2020.

A hearing will take place on 11 June 2021. After a reopening of debates will be followed by a new round of conclusions.

In its decision of 2 February 2022 (’the Contested Decision’), the Dispute Resolution Chamber of the GSA ruled that IAB Europe acts as a data controller in respect of the registration of the consent signal, objections and preferences of individual users by means of a unique Transparency and Consent (TC) String, which, according to the Dispute Resolution Chamber, is linked to an identifiable user. IAB Europe disputes this.

The draft decision prepared by the GBA has been examined under the cooperation mechanism of the AVG (the "one-stop shop" mechanism)

In the Contested Decision, the GSA further ruled as follows:

Order the defendant, pursuant to Article 100(1)(9) of the WOG, to bring the processing of personal data within the framework of the TCF into line with the provisions of the AVG by

a. Provide a valid legal basis for the processing and dissemination of users’ preferences within the framework of the TCF, in the form of a TC String and a euconsent-v2 cookie, as well as prohibit the use of legitimate interests as a basis for the processing of personal data, by organisations participating in the TCF in its current form, through the Terms of Use, in accordance with Articles 5.1.a and 6 of the AVG,-

b. implement effective technical and organisational control measures to guarantee the integrity and confidentiality of the TC String, in accordance with Articles 5.1 j, 24, 25 and 32 of the AVG,-

c. Maintain a strict screening of organisations that join the TCF in order to ensure that participating organisations meet the requirements of the AVG in accordance with Articles 5.1 j, 24, 25 and 32 AVG;

d. take technical and organisational measures to prevent that consent is ticked by default in the CMP interfaces and that participating vendors are automatically allowed on the basis of a legitimate interest, in accordance with Articles 24 and 25 AVG

e. impose on CMPs to adopt a uniform and AVG-compliant approach to the information they submit to users, in accordance with Articles 12 to 14 and 24 of the AVG

f. supplement the current register of processing activities by including the processing of personal data in the TCF by IAB Europe, in accordance with Article 30 of the AVG;

g. To carry out a data protection impact assessment (DIA) with regard to the vender activities under the TCF and their impact on the processing activities carried out under the OpenRTB system, and to adapt this DIA to future versions or amendments to the current version of the TCF, in accordance with Article 35 of the AVG;

h. Appoint a Data Protection Officer (DPO) in accordance with Articles 37 to 39 of the AVG.

These compliance measures shall be implemented within six months following the validation of an action plan by the Belgian Data Protection Authority, which shall be submitted to the Litigation Chamber within two months of this decision (note: no later than 2 April 2022). Failure to comply with the above-mentioned time limits is subject to a penalty of EUR 5,000 per day, pursuant to Article 100, § 1, 12° of the WOG.

Impose on the defendant, on the basis of Article 101 of the WOG, an administrative fine of EUR 250,000."

II. Object of the claims

1. The applicants’ action is directed against:;

Declare the Appellant’s appeal admissible and well-founded;

- Accordingly, annul the contested decision No 21/2022 of 2 February 2022 in Case No DOS- 201901377;

- And again, to rule that the Appellant is not at fault;

- order the GBA and the complainants to pay the costs of the proceedings, including legal costs and fees, the latter being estimated at EUR 1 440.00

2. The GBA asks the Market Court:

To do justice with full jurisdiction:

- Declare the substantive grievances nos. 9 to 19 of IAB Europe unfounded;

- Consequently, a declaration that IAB Europe has infringed the following provisions: Article 5.1.a of the AVG; Article 6 of the AVG; Article 12 of the AVG; Article 13 of the AVG; Article 14 of the AVG; Article 5.2 of the AVB; Article 5.3 of the AVB; Article 5.3 of the AVMS; Article 5.3 of the GC. 13 AVG; Article 14 AVG Article 24 of the AVG; Article 25 of the AVG; Article 5.1.f. of the AVG; Article 32 of the AVG; Article 30 of the AVG; Article 35 of the AVG; Article 37 of the AVG, in the manner set out in recital 535 of the contested decision No 21/2022 of 2 February 2022 of the Dispute Resolution Division of the GBA;

- Also declare procedural grievances nos. 1 to 8 of IAB Europe to be unfounded;

- Accordingly, confirm the legality of contested decision No 21/2022 of 2 February 2022 and, in particular, the penalties imposed thereon on IAB Europe (contained in the operative part of the decision, pp. 138-139);

- In any event, declare that IAB Europe’s claim is unfounded;

- In subsidiary order, refer the following questions to the Court of Justice of the European Union for a preliminary ruling pursuant to Article 267 TFEU:

1. "Should Articles 4(7) and 24(1) of Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC, read in conjunction with Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, aidus be interpreted as meaning that a sectoral organisation must be qualified as a data controller where it has submitted data to its processor? /eden offers a consent management system which, in addition to a binding technical framework, contains mandatory rules specifying in detail how this consent data, which constitutes personal data, is to be stored and disseminated?

2. Does the answer to question (a) lead to a different conclusion if that sectoral organisation itself does not have access to the personal data processed by its members within this system?"

- In any event, order IAB Europe to pay the costs of the proceedings, including the basic indexed amount of the legal fees for non-monetary claims.

3. The original complainants intervened voluntarily and they are asking the Market Court:

To grant the applicants the act of their custodial voluntary intervention;

For the reasons set out by the CBA and the applicants, declare IAB Europe’s action to be unfounded, or at least refer the following questions to the Court of Justice for a preliminary ruling :

"1) a) Must Article 4.1 of Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC, read in conjunction with Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, be interpreted as meaning that a character string which purports to capture the preferences of a specific internet user in connection with the processing of his personal data in a structured and machine-readable manner constitutes personal data within the meaning of the aforementioned provision in relation to (1) an industry body which provides its members with a mechanism whereby it prescribes to them in a detailed and binding manner the practical and technical manner in which that character string must be generated, stored and/or distributed, and (2) the parties which have implemented that mechanism on their websites or in their apps and thus have access to that character string?

b) Does it make a difference if the implementation of the mechanism means that this character string is available together with an IP address?

2) a) Must Articles 4.7 and 26.1 of Regulation 2016/679 of 27 April 2016 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data and repealing Directive 95/46/EC, read in conjunction with Articles 7 and 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, be interpreted as meaning that an industry association which makes available to its members a mechanism whereby it prescribes in a detailed and binding manner the practical and technical procedures for the generation, storage and/or dissemination of personal data, must be regarded as a controller in respect of the processing of those personal data, together with those members which implement that mechanism on their website in accordance with the specified rules.eed rules on their website/apps and/or in their commercial activities?

b) Does it make a difference if this sector organisation itself does not have access to the personal data processed by means of the dot mechanism via the website/apps and/or in the commercial activities of its members?

III. Means supplied by the parties

The applicants develop the following means:

FIRST GRIEVANCE: SEVERAL COMPLAINTS ARE INADMISSIBLE

SECOND GRIEVANCE: THE INSPECTION REPORT INFRINGES THE APPELLANT’S RIGHT OF DEFENCE AND IS INSUFFICIENTLY REASONED, INCOMPLETE AND BIASED. THIRD GROUND OF APPEAL: ARTICLES 100 AND 101 OF THE WOG ON PENALTIES VIOLATE THE PRINCIPLE OF PROPORTIONALITY AND THE PRINCIPLE OF THE MATERIAL LEGALITY, AS LAID DOWN IN ARTICLES 6 AND 7 OF THE EEC AND ARTICLE 47 OF THE EU CHARTER. FOURTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE ARBITRAL TRIBUNAL DID NOT GIVE ADEQUATE REASONS FOR THE ADMINISTRATIVE FINE IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CRITERIA OF ARTICLE 82.2 OF THE AVG

FIFTH GRIEVANCE: THE INTERNAL RULES OF THE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT CHAMBER INFRINGE THE PRINCIPLE OF THE FORMAL LEGALITY OF CRIMINAL PENALTIES, GUARANTEED BY ARTICLES 12 AND 14 OF THE CONSTITUTION, AS WELL AS THE RIGHT OF DEFENCE. SIXTH PLEA IN LAW: THE APPOINTMENT OF THE MEMBERS OF THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION CHAMBER IS CONTRARY TO ARTICLE 53 OF THE AVG AND CONTRARY TO PUBLIC POLICY SEVENTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE WAY IN WHICH THE DISPUTES CHAMBER HANDLED THE PROCEEDINGS IS CONTRARY TO ITS DUTIES AND POWERS AS DATA PROTECTION AUTHORITY UNDER THE WOG AND AVG , INFRINGES THE APPELLANT’S RIGHTS OF DEFENCE AND DISREGARDS THE PRINCIPLE OF DUE CARE AS A PRINCIPLE OF SOUND ADMINISTRATION EIGHTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE CONTESTED DECISION IS NOT ADEQUATELY REASONED. NINTH GRITE: THE WAY THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION CHAMBER DECIDES THAT TC STRINGS ARE PERSONAL DATA IS INSUFFICIENTLY NUANCED AND REASONED

TENTH GRIEVANCE: THE CONTESTED DECISION IS WRONG TO ALLEGE THAT THE APPELLANT PROCESSES PERSONAL DATA

ELEVENTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE CONTESTED DECISION WRONGLY CONCLUDES THAT THE APPELLANT IS A CONTROLLER IN RESPECT OF TC STRINGS

TWELFTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE CONTESTED DECISION WRONGLY CONCLUDES THAT THE APPELLANT IS A JOINT CONTROLLER FOR THE PROCESSING OF TC STRINGS AND RELATED DATA THIRTEENTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE CONTESTED DECISION WRONGLY CONCLUDES THAT THE APPELLANT NEEDS A VALID LEGAL BASIS AND THAT NO LEGAL BASIS EXISTS FOR PROCESSING TC STRING AND OPENRTB DATA

FOURTEENTH GRIEVANCE: THE DISPUTES COMMITTEE WRONGLY DECIDED THAT THE APPELLANT WAS IN BREACH OF ITS DUTY OF TRANSPARENCY FIFTEENTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE CONTESTED DECISION WRONGLY CONCLUDES THAT THE APPELLANT BREACHED ITS OBLIGATIONS CONCERNING SECURITY, INTEGRITY AND DATA PROTECTION BY DESIGN AND DEFAULT

SIXTEENTH GRIEVANCE: THE APPELLANT IS NOT OBLIGED TO CARRY OUT A DATA PROTECTION IMPACT ASSESSMENT

SEVENTEENTH GRIEVANCE: THE APPELLANT DOES NOT HAVE TO APPOINT A DATA PROTECTION OFFICER

EIGHTEENTH GROUND OF COMPLAINT: THE APPELLANT HAS NO LEGAL OBLIGATION TO FACILITATE THE EXERCISE OF THE RIGHTS OF THE PERSONS CONCERNED

NINETEENTH COMPLAINT: THE APPELLANT IS NOT OBLIGED TO HAVE A REGISTER OF PROCESSING ACTIVITIES AND, IN ANY EVENT, THIS REGISTER IS NOT INCOMPLETE.

The GBA develops defences in relation to the means put forward by the applicants.

FIRST RESPONSE: The Dispute Resolution Chamber was duly convened by the First-line Service - Your Court has no jurisdiction to rule on the decisions of the First-line Service regarding the admissibility of complaints - The complaints filed abroad were transferred to the GBA applying the cooperation procedure provided for under Article 56 AVG - These complaints were transferred to IAB Europe in a tool which IAB Europe is competent (defence against the first head of complaint of IAB Europe)

SECOND GROUND: IAB Europe had timely and adequate knowledge of the facts and the infringements committed against it and was able to defend itself adequately against them - The Inspectorate has no power to sanction and its task is limited to establishing findings and transmitting them to the Dispute Resolution Chamber - The Court is not bound by the findings of the Inspectorate and the alleged defects of the Inspectorate report do not therefore automatically affect the legality of the contested decision - IAB Europe does not show that the Inspectorate is biased - In any event, the guarantees of Article 6 ECHR are guaranteed by the review with full jurisdiction of the Court (defence of the second ground of complaint of IAB Europe)

THIRD GROUND OF DEFENDANCE: Articles 100 and 101 of the WOG in conjunction with Article 83 of the AVG, which the Court interprets and applies in accordance with the case-law of the Court of Justice, the WP29 Guidelines and the general principles of sound administration, are not contrary to Articles 6 and 7 of the ECHR and Article 47 of the EU Charter. 150 AVG - A wide margin between the upper and lower limits of an administrative fine is not incompatible with the principle of criminal legality (defence against the third ground of complaint of IAB Europe)

FOURTH GROUND: The administrative fine imposed is appropriate in fact and in law, applying the criteria set out in Article 83(2) AVG The administrative fine imposed is disproportionate in light of the breaches of the basic principles of the AVG identified and the circumstances of the case (defence against IAB Europe’s fourth GROUND)

FIFTH GROUND: The procedure of the Dispute Chamber is a sui generis administrative law procedure and the decisions of the Dispute Chamber can, according to Article 6.1 ECHR, be appealed before an ’independent and impartial tribunal established by law’ which decides with full jurisdiction - Articles 12 and 14 of the Constitution did not require any data/all aspects of the procedure of an organ of active administration which can impose administrative fines to be regulated by the legislator itself. In this respect, all ’essential elements’ of the procedure before the Dispute Chamber were in any case laid down by the legislator itself in the WOG - The delegation on the RIO in article 33, §2 WOG meets the requirement of article 52 AVG that the supervisory authority must be able to act completely independently in the performance of its duties and powers under the AVG - Moreover, the RIO was submitted for approval to the Chamber of Representatives, so that its provisions were in any event controlled by a democratically constituted assembly (defence against the fifth grievance of IAB Europe)

SIXTH PRAYER: Your Court has no jurisdiction to rule on the legality or otherwise of the appointment of the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber by the Chamber of Representatives.

- The alleged irregularity of the appointment of the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber does not affect the lawfulness of the contested decision - There is no indication that the relevant members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber are not independent and impartial - The right to a fair trial is respected guaranteed in any event by the control, with unlimited jurisdiction, of your Court (defence of the sixth grievance of IAB Europe)

SEVENTH PRAYER: IAB Europe did not substantiate (and does not substantiate) which new elements required a so-called additional examination - the Dispute Chamber was able to take into account all elements of proof a charge, both on the part of the complainants and the lnspectorate, as long as the the rights of defence in the matter were adequately guaranteed - the parties had ample opportunity to argue their case on the allegations and charges, which were properly and timely known to IAB Europe - an additional investigation by the Inspectorate was therefore by no means necessary, nor was such an investigation possible, having regard to the time-limits under Article 96 WOG (defence against the seventh grievance of IAB Europe)

EIGHTH PLEA IN LAW: the contested decision is sufficiently reasoned - The formal obligation to state reasons does not require an administrative decision to disprove every argument put forward by a party to the proceedings in order to be conclusive - Substantial grounds are sufficient and exist in the present case - The formal obligation to state reasons is, moreover, a ’do-nothing’ rule and IAB Europe has not demonstrated any harm to its interests - It is apparent from IAB Europe’s complaints that it was able to challenge the contested decision in full knowledge of the facts (defence of the eighth complaint of IAB Europe)

CONTENTS

NEGTH DEFENSE: The TC Strings do constitute personal data (defence against the ninth grievance of IAB Europe)

First reason: CMPs can link TC Strings to IP addresses

Second reason: TCF dealers/contractors can also identify the user by other data

Third reason: IAB Europe has access to information that allows TCF participants to identify users

Fourth reason: the purpose of the TC String is to identify the user Tenth plea in law: personal data are processed in the context of the TCF (defence against the tenth grievance of IAB Europe)

ELFTH GROUND: IAB Europe is a data controller in respect of the processing of TC Strings (defence against the eleventh grievance of IAB Europe)

a. IAB Europe has a decisive influence on the processing of TC Strings

b. IAB Europe determines the purposes of the processing of TC Strings within TCF

c. IAB Europe determines the means of processing TC Strings

IAB Europe determines how the TC String is generated, modified and read out (points i and ii)

IAB Europe determines the storage location and method for both service-specific as globally scoped consent cookies IAB Europe determines who receives the personal data

IAB Europe defines the criteria with which the retention periods for TC Strings can be determined

d. IAB Europe has never previously been held by other supervisory authorities to be a data controller does not affect the lawfulness of the contested decision

e. A TCF is not a code of conduct within the meaning of section 40-41 of the AVG.

f Question referred

SECOND GROUND: IAB Europe is a joint controller for the processing of TC Strings and other data (defence against the twelfth grievance of IAB Europe)

IAB Europe is a ’joint controllers’ CMPs are ’joint controllers’

Publishers are ’joint controllers’

Adtech vendors are ’joint controllers’

THIRTEEN GROUND: IAB Europe must have a valid legal basis for processing TC Strings and OpenRTB data but no such legal basis is available (defence against the thirteenth GROUND of IAB Europe)

IAB Europe has no legal basis for the registration of users’ consent, objections and preferences through TC Strings

IAB Europe does not require a legal basis for the collection and dissemination of personal data in the context of RTB

The contested decision rightly finds that consent is not a valid basis for the processing operations in the OpenRTB authorised by the TCF

The contested decision correctly holds that the legitimate interest of the participating organisations does not outweigh the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of the persons concerned

Defendant: IAB Europe is in breach of its transparency picht (defence against the fourteenth plea of IAB Europe)

FIVE GROUND: IAB Europe is in breach of its obligations in relation to security, integrity and data protection (defence against the 15th grievance of IAB Europe)

IAB Europe, as a controller, is subject to the obligations in Article 24.1, Article 5.1.f, Article 32 and Chapter V of the AVG.

IAB Europe breached the security obligation

SIXTEENTH DEFENSE (Defence against the sixteenth to nineteenth grievances of IAB Europe)

The complainants, as voluntary intervening parties, support the position of the GBA and they put forward the following (defence) pleas:

Plea 1: The complaint lodged by the applicant Fundacja Panoptykon is admissible. First of all, her complaint submitted to the Polish supervisory authority pursuant to Article 77.1 AVG did not have to be drawn up in a Belgian language, since Article 60 WOG does not apply to complaints which supervisory authorities from other EU Member States forward to the GBA as leading supervisory authority on the basis of the one-stop shop mechanism provided for in Article 56 AVG. Indeed, Article 60 of the CPC literally provides, and must in any event be interpreted as meaning, that the admissibility requirement set out therein that a complaint be drawn up in one of the national languages only applies to complaints lodged directly with the CBA; otherwise, that article would make the one-stop shop mechanism impossible or extremely difficult to implement in practice, thereby infringing the EU law principle of sincere cooperation and the EU law principle of effectiveness. Second, Fundacja Panoptykon was able to lodge the complaint with the Polish Supervisory Authority on behalf of Ms Katarzyna Szymielewicz under Article 80.1 AVG and Ms Katarzyna Szymielewicz’s letter of instruction was annexed to the complaint. Third, IAB Europe does not provide any argument as to why Fundacja Panoptykon could not be considered as a complainant and a party. (Rebuttal to the first grievance of IAB Europe)

Plea 2: The reasoning in the report of the lnspectorate of 13 July 2020 is indeed adequate. Moreover, the Dispute Resolution Chamber could also rely on the extensive and detailed conclusion and documents of the complainants. In addition, in its summary conclusion before the Dispute Resolution Chamber of 25 March 2021, IAB Europe did not indicate which technical matters in the investigative reports of the Inspectorate or in the conclusion of the complainants of 18 February 2021 allegedly inaccurate, so that it can be assumed that it did not contain any technical inaccuracies. (Rebuttal of the second head of claim of IAB Europe)

Means 3: The report of the Inspectorate is not incomplete or biased. Nor does IAB Europe give any concrete example. Moreover, it is not the Inspectorate but the Dispute Resolution Chamber that makes a decision, the Dispute Resolution Chamber could also rely on the extensive and detailed claim and documents submitted by the complainants, and IAB Europe did not indicate in its summary conclusion before the Dispute Resolution Chamber of 25 March 2021 which technical matters in the investigative reports of the Inspectorate or in the claim of the complainants of 18 February 2021 are allegedly incorrect, so that it may be assumed that there are no technical inaccuracies or omissions in them. (Rebuttal of the first head of claim of IAB Europe)

Ground 4: The way in which the CPC dealt with the proceedings does not conflict with its duties and powers as a data protection authority under the WOG and the AVG, does not violate IAB Europe’s rights of defence, and does not disregard the principle of due care. After all, the WOG contains both an inquisitorial and an adversarial procedure, and the Dispute Chamber may also rely on the conclusions and evidence of a complainant without having to have all the facts and allegations contained in a complainant’s conclusions examined by the lnspectorate. Neither Articles 63 and 94 WOG nor Article 57.1.f AVG oblige the Litigation Chamber to have all the facts and allegations contained in a complainant’s claim examined by the Inspectorate before making a decision. Article 57.1.f AVG does not even have direct effect, so IAB Europe cannot derive any rights from it. The only relevant test is whether the equality of arms and the defendant’s right of defence have been respected. This is the case when (1) the Defendant knows, before its last conclusion, which facts and articles of law have been infringed by the Complainant and/or the Inspectorate, (2) it has been able to conclude on them last in writing so that it has the last word, and (3) the Dispute Resolution Chamber bases its decision exclusively on the pleas and arguments from the conclusions and documents of the parties and/or the report of the Inspectorate. In that case, the defendant has been able to defend himself against all factual and legal pleas in law and arguments in the conclusions of the complainant and/or the report of the Inspectorate, and the decision can be reviewed by the Market Court in relation to the pleas in law and arguments in the conclusion of the defendant. In the present case, those conditions were fulfilled, so that equality of arms and IAB Europe’s rights of defence were respected. (Rebuttal of the seventh grievance of IAB Europe)

Means 5: IAB Europe is the data controller in respect of the processing of personal data in the TCF. Indeed, the TCF itself, for which IAB Europe expressly states that it is responsible, obliges the participants to process personal data for the alleged purpose of bringing the underlying processing of personal data through the OpenRTB auction system into line with the AVG. (Rebuttal of the ninth, tenth and eleventh heads of claim of IAB Europe)

Ground 6: IAB Europe’s processing violates the fundamental principles of purpose limitation, proportionality and necessity. Indeed, IAB Europe’s processing operations were not collected for legitimate purposes and result in the sharing of personal data on an immense scale with all kinds of recipients, without such sharing being in any way useful to bring the processing operations in the context of the OpenRTB auction system in line with the AVG. IAB Europe consequently also breaches its duty of accountability and its obligation to develop the TCF in a manner that ensures data protection by design. (Infringement of Articles 5 and 25 of the AVG) (rebuttal of the 15th grievance of IAB Europe)

Ground 7: IAB Europe’s processing of personal data in the TCF violates the basic principle of fair, lawful and transparent processing. It has no legal basis for the processing, has obtained the personal data in a misleading manner and does not provide the complainants or any other data subjects with the legally required information about its personal data processing operations. (infringement of Articles 5, 6, 12, 13 and 14 TFEU) (refuting the thirteenth and fourteenth pleas in law of IAB Europe)

Ground 8: IAB Europe infringes the principle of integrity and confidentiality because it shares personal data within the TCF with an indefinite number of recipients without verifying whether those recipients actually provide the necessary guarantees to protect the personal data against unauthorised or unlawful processing. (infringement of Articles 5 and 32 TFEU) (refuting the fifteenth grievance of IAB Europe)

Means 9: IAB Europe infringes the conditions for the transfer of personal data to third countries, as it has set up the TCF in such a way that personal data such as the TC String are systematically transferred to numerous third countries without adequate protection being provided for those transfers. (Infringement of Article 44 TFEU)

IV. Legal framework

AVG

Articles 5.1.a and 5.2 (principles of fairness, transparency and accountability);

Article 6.1 (lawfulness of processing)

Article 9.1 and 9.2 (processing of special categories of personal data);

Article 12.1 (transparency of information, communications and modalities for exercising data subjects’ rights)

Article 13 (information to be provided when personal data have been obtained from the data subject);

Article 14 (information to be provided when personal data have not been obtained from the data subject);

Article 24.1 (responsibility of the controller);

Articles 32.1 and 32.2 (security of processing).

Article 30 (register of processing activities);

Article 31 (cooperation with the supervisory authorities) Article 24.1 (responsibility of the controller);

Article 37 (appointment of a data protection officer.

Article 52 (independence of the supervisor)

WOG

Article 33

Article 58 et seq. Article 93, 95, 98, 99 and 108

Article 96

Articles 100 and 101

V. Discussion and assessment by the Market Court

As a preliminary remark, regarding the rejection of the supplementary note from IAB

During the oral hearing before the Market Court, the GBA reported that, around midnight on 29 June 2022, it received an additional note from IAB Europe. This written note apparently contains certain suggestions for a preliminary ruling. The GBA has not been able to respond to this in writing and therefore requests the exclusion of this written document.

IAB does not put forward an adequate defence against this.

Pursuant to article 747 § 2, sixth paragraph Ger. W., submissions that are filed with the court registry or sent to the other party after the expiry of the time limits are automatically excluded from the debates. In doing so, the Market Court may not assess the interest of the party concerned and, moreover, a party has an interest under the law that a late submission is automatically excluded from the debate.

Pursuant to article 740 Ger. W., all pleadings, notes or documents that have not been submitted at the latest at the same time as the conclusions are automatically excluded from the debates.

Accordingly, the additional note which IAB Europe (only) lodged and transferred the day before the oral hearing should be excluded from the debate.

a. Admissibility of the actions

The story has been set regularly by IAB Europe in terms of form and deadline and there is no dispute about that.

b. The procedural grievances

FIRST GRIEVANCE: SEVERAL COMPLAINTS ARE INADMISSIBLE

In the context of its first grievance, IAB Europe refers to the conditions of admissibility of complaints, included in Article 60 of the WOG. IAB Europe argues that the persons who lodged the complaints (lodged abroad) with references DOS-2019-01377, DOS-2019-04052, DOS-2019- 04210 and DOS-2019-04269 cannot be regarded as "complainants" within the framework of the proceedings before the Dispute Resolution Chamber or as "parties" within the meaning of Articles 93, 95, 98, 99 and 108 WOG. According to IAB Europe, the proceedings before the Dispute Resolution Chamber were thus unlawfully initiated on the basis of several inadmissible complaints. IAB Europe is of the opinion that the Dispute Resolution Chamber should therefore exclude the reply of these persons dated 18 February 2021 from the debates, and that these persons therefore had/have no interest in a measure taken by the Dispute Resolution Chamber against IAB Europe. Finally, IAB Europe - referring to a note of the Dispute Resolution Chamber dated 12 February 2021 regarding "the position of the complainant in the procedure before the Dispute Resolution Chamber" - argues that the GBA should in any event check the aforementioned complaints against all formal admissibility conditions of article 58 et seq. of the WOG (including the requirement that the complaint must be drawn up in one of the Belgian national languages).

The GBA makes the following arguments (in summary):

- These are vague assertions by IAB Europe, which has thus failed in its duty to assert and its burden of proof;

- The Dispute Resolution Chamber was regularly convened by the First-line Service (art. 62 & 92 WOG)

- The Market Court has no jurisdiction to adjudicate on the decisions of the Primary Care Unit

- The formal admissibility requirements (incl. language art. 60 WOG) only apply to complaints filed in Belgium with the GBA

- Foreign complaints were forwarded to IAB Europe in a language that it knows (in particular English) and has used itself.

The Market Court is considering:

The Court of Arbitration shall notify the parties of its decision and of the possibility to lodge an appeal with the Market Court within a period of thirty days from the notification.

An effective remedy must be available against all decisions of the GBA. In that regard, Article 78(1) of the AVG provides that, without prejudice to any other form of administrative or non-judicial recourse, any natural or legal person must have the right to an effective remedy before a court against a legally binding decision of a supervisory authority which concerns that person.

The Belgian legislator must therefore clearly determine which court is competent to take cognisance of the ’effective remedy’. With regard to the GBA, the Market Court has only been granted jurisdiction by the Belgian legislator to rule on decisions of the Dispute Resolution Chamber of the GBA.

It is the Primary Service of the GBA that decides whether a complaint is admissible or not and the Market Court - indeed as rightly stated by the GBA itself - has no jurisdiction to take cognisance of an ’effective remedy’ regarding a ’decision’ of the Primary Service. If one considers the nature of the decision (and one would qualify it as administrative), an appeal could be lodged with the Council of State.

The formal admissibility requirements provided for in Article 58 of the WOG, and more specifically the requirement that a complaint be drawn up in one of the national languages, apply exclusively - as the GBA also rightly maintains - to the complaints submitted directly to the GBA.

In the contested decision, the Dispute Resolution Chamber correctly referred to Article 77.1 AVG, pursuant to which data subjects have the right to lodge a complaint in the Member State in which they habitually reside, have their place of work or where the alleged infringement was committed. The four complaints in English referred to by IAB Europe were not submitted directly to the CRA, but to the national supervisory authorities competent for each of the complainants, in accordance with the locally applicable language legislation. In this case, the four complaints were submitted respectively to the Polish regulator, the Slovenian regulator, the Italian regulator and the Spanish regulator, which then referred them to the Belgian GBA. The same happened with a complaint filed in the Netherlands. Four complaints were also filed in Belgium against IAB Europe. There is no conclusive evidence that these nine complaints, or 4/5 of them as IAB Europe maintains, are inadmissible.

As for the language in which the parties express themselves, Article 30 of the Constitution guarantees linguistic freedom. It is clear from the documents submitted that IAB Europe understands English and uses it itself as one of its working languages.

As regards the language of the proceedings before the Data Protection Authority, i.e. the language in which the CPC addresses the parties, Article 57 of the WOG stipulates in the context of the complaints procedure that "the Data Protection Authority shall use the language in which the proceedings are conducted according to the needs specific to the case". The Litigation Chamber therefore applies article 57 of the WOG and, read in conjunction with article 60 of the WOG[1], the proceedings are conducted in one of the national languages in Belgium (in this case Dutch).

In view of the foregoing, IAB Europe’s first ground for complaint is unfounded.

SECOND GRIEVANCE: THE INSPECTION REPORT INFRINGES THE APPELLANT’S RIGHT OF DEFENCE AND IS INSUFFICIENTLY REASONED, INCOMPLETE AND BIASED.

In the first part of its plea in law, IAB Europe claims that its rights of defence have been infringed because the inspection report did not specify the alleged infringements of the AVG in a sufficiently precise and detailed manner, nor did it mention the specific acts which could be classified as infringements of the AVG. The Inspectorate also failed to identify a specific actor in relation to a clear data processing activity. IAB Europe considers that, as a result, it was not in a position to clearly understand the scope of the allegations and to prepare an adequate defence. In addition, IAB Europe considers that the inspection report, as an ’administrative decision’, also violates the substantive and formal obligation to state reasons, for the same reasons. In this context, IAB Europe stresses that the entire procedure was conducted on the basis of this report, which determined the scope of the prosecution and therefore of the defence.

In its second part of the plea in law, IAB Europe submits that the basic principles of loyalty, impartiality and independence - which apply to the Public Prosecutor’s Office in criminal cases - also apply to the Inspectorate. IAB Europe submits that ’the Inspectorate Report’ does not contain an objective and impartial summary of all the relevant elements of the investigation - including ’a number of particularly relevant exculpatory elements of which the Inspectorate was aware or should have been’ - and that the report is also full of insulting and unsubstantiated statements. Given the bias with which the investigation was conducted and with which the Inspection Report was drafted, IAB Europe claims that its presumption of innocence was irrevocably breached by the GBA.

The GBA disputes this and states (in summary) that:

- The right of defence does not require that all charges be bundled into one document at the outset (e.g. inspection report or complaint)

- What matters is that the defendant had timely and adequate knowledge of the charges. + was given the opportunity of defending itself against it + if the defendant had the last word: assessment in globo

- The chronology of the administrative file shows that IAB Europe was aware of the charges from the outset and this is reflected in its conclusions lnspection report: summary of 6 findings + relevant provisions AVG + reference to very detailed technical reports lnspection Service

- The outline of the debate was further delineated in the parties’ conclusions

- Allie charges were also explicitly mentioned again in the sanction form.

- The contested decision was strictly limited to the scope of the complaints and the inspection reports

The Market Court considers that it appears from the administrative file that the file in this case was submitted to the Inspectorate by the GBA Dispute Resolution Chamber. This was done on 19 March 2019 (document A003 from the administrative file) and on the basis of section 96(1) WOG:

§ 1. The request of the Chamber of Disputes, mentioned in Article 94, 1°, to carry out an investigation must be handed over by the front-line service to the Inspector General of the Inspectorate within thirty days after the complaint was lodged with the Chamber of Disputes.

The investigative powers must be exercised by the Inspectorate for the purpose of supervision as provided for in Article 4 para. 1 WOG. This refers to the supervision of compliance with the basic principles of personal data protection under the Data Protection Act and the laws containing provisions on the protection of the processing of personal data. This relates to the principle of finality that must be applied by the inspectorate in the exercise of their powers. Moreover, the means used in the exercise of the investigative powers must be appropriate and necessary (Article 64 para. 2 WOG). This provision concerns the principle of proportionality that the inspectorate must apply in the exercise of its powers. The various investigative measures can give rise to an official report establishing an infringement. This report has evidential value until the contrary is proven (Article 67 par. 1 WOG).

Article 91 para 1 WOG states: When the Inspector General and the inspectors consider their investigation complete, they shall prepare their report and attach it to the file.

On 13 July 2020, the Inspectorate communicated its report, Document 61 of the administrative file, to the Litigation Chamber. This report was originally communicated in French and then translated into English and Dutch.

First part: The inspection report violates the right of defence and is not sufficiently reasoned

IAB Europe’s rights of defence were not infringed in the context of the drafting of the inspection report. IAB Europe can hardly claim that it did not receive timely and/or adequate notice of the investigation by the inspectorate or that it was prevented from defending itself adequately in that context. The Inspectorate makes reference in the report to the following investigative measures:

- Contact with the processing agent (documents no. 15, 17, 18, 22, 26, 27, 29, 37, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59 and 60 of file DO5-2019-01377)

- technical analysis report on the mechanism "Open Realtime Bidding API Specification" version 2.5 dated 04/06/2019 (exhibit no. 24 of file DOS-2019-01377)

- Technical analysis report for information of the lnspectorate on the use of personal data via OpenRTB v3.0 and on the processing of personal data within the framework of the Transparency and Consent Framework V2.0 dated 06/01/2020 ( Document no. 53 in file DO5-2019-01377).

- Online searches and thorough /reading of the documents on the websites IAB Europe, IAB Tech Lab and Interactive Advertising Bureau, Inc. (hereafter abbreviated to "IAB, inc.") (documents nos. 30 to 36, 38, 41 to 50 of file DO5-2019-01377).

- Searches online or in libraries and thorough /reading of documents created / by the Information Commissioner’s Office (hereinafter "ICO") (Exhibits 21 and 52 in File DOS-2019-01377) or by scientific researchers specialised in the field of RTB.

Some 15 emails were exchanged by the inspectorate with IAB Europe.

The inspection report contains a list of 6 findings with reference to the relevant AVG provisions and with reference to detailed technical reports of the inspectorate

The question of whether a subordinate has been able to adequately defend himself - prior to a contested government decision - should not be checked against specific formalities, but can (and must) be assessed in globo.

The Market Court shall verify whether the decision of the GBA Dispute Resolution Chamber is sufficiently reasoned.

In order to verify whether a decision is adequately reasoned, the data protection rules must be assessed in terms of their finality and not in terms of a purely exegetical and restrictive textual interpretation. Indeed, the reasoning of the Dispute Resolution Chamber of the GBA must be able to be reviewed by the Market Court in relation to the pleas or arguments developed by the person concerned in his/her submission. The Court assesses compliance with the substantiation requirement of the Open Government Act. Adequacy of the statement of reasons means that the reasons must be relevant, i.e. clearly related to the decision, and substantial, i.e. the reasons must be sufficient to support the decision.

The above principles of reasoning do not apply in an absolute manner to inspection reports only to the extent that the content of such reports would have been reproduced verbatim in the contested decision.

IAB Europe does not substantiate that the inspection reports violate its rights of defence, and / or in itself would be insufficiently reasoned. This part of the plea is unfounded.

Second part: The Inspection Report is incomplete and biased

Contrary to IAB Europe’s assertion, the Inspectorate is not an administrative authority of criminal law within the meaning of Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), as it has no power to impose sanctions and its remit is limited to making findings and transmitting them to the Dispute Settlement Chamber by means of its report.

The obligation of independence invoked by IAB Europe therefore applies (only) to the inspectors (and not as such to the inspection report itself), as it also applies to the members of the Board of Directors of the GBA, the members of the Knowledge Centre and the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber. These persons may not, directly or indirectly, receive or ask for instructions within the limits of their powers. They are also forbidden to be present at a deliberation or decision regarding files in which they have a personal or direct interest or in which their relatives by blood or marriage up to the third degree have a direct personal interest (see Charter of the Inspection Service version 1.0 of August 2021 available on the webpage https://www.gegevensbeschermingsautoriteit.be/burger/de-autoriteit/visie-missie). IAB Europe does not indicate any concrete problem regarding the independence of inspectors.

If the investigation shows that there are sufficient elements to ’prosecute’ the facts administratively and to take corrective action, it will be decided in principle to hand over the file to the chairman of the Disputes Chamber and this is indeed what happened in this case.

If the inspectorate is involved in the file, it is informed that the file is in state (ready for processing). If necessary, the inspectorate can also be heard by the Dispute Resolution Chamber (article 48 par. 2 of the Rules of Internal Procedure of the GBA). Even if the inspection report is incomplete, which is not proven by IAB Europe, there is still an opportunity for the Dispute Resolution Chamber to ’put things right’. In the contested decision (§209), the Dispute Resolution Chamber correctly argues that it is not bound by the findings of the Inspectorate.

This part of the plea is unfounded.

THIRD GROUND OF APPEAL: ARTICLES 100 AND 101 OF THE WOG ON PENALTIES VIOLATE THE PRINCIPLE OF PROPORTIONALITY AND THE PRINCIPLE OF THE MATERIAL LEGALITY, AS LAID DOWN IN ARTICLES 6 AND 7 OF THE EEC AND ARTICLE 47 OF THE EU CHARTER.

IAB Europe’s position is as follows:

The measures and fines which the GBA is authorised to impose in the context of Articles 100 and 101 of the WOG, read in conjunction with Article 83 of the AVG, must be classified as sanctions of a criminal nature within the meaning of the international treaties on human rights, such as the ECHR and the EU Charter, having regard to the very nature of the infringements and the nature and severity of the penalties.[2] The criminal nature of the sanctions that may be imposed by the GBA is also confirmed by legal doctrine.[3]

Consequently, Articles 6 and 7 of the ECHR and Article 47 of the EU Charter are applicable to these sanctions. These articles impose specific requirements on the substantive/legality and proportionality of a sanction. The first principle means that the sanction must be foreseeable on the basis of a specific and sufficiently precise legal provision; the second principle means that the severity of a sanction must be proportionate to the offence.[4]

In this respect, Article 101 WOG only provides that the Dispute Resolution Chamber "may decide to impose an administrative fine on the parties transported in accordance with the general conditions set out in Article 83 AVG."

Article 83(4) to (6) AVG allows for the imposition of very high maximum fines for certain categories of infringements, which can be up to €10 000 000 or €20 000 000, or even up to 2 to 4 per cent of the total annual turnover of an organisation. This creates a very wide margin between the minimum and maximum amount of possible administrative sanctions. Moreover, the offences that may lead to such fines are very broadly defined, namely by referring in general terms to certain obligations under the AVG.

According to the Council of State, a very wide margin between the minimum and maximum amount of administrative sanctions of a criminal nature, whereby all infringements are put on an equal footing and the law makes no distinction as to the severity of the sanction, is contrary to the fundamental principles of substantive legality and proportionality.[5] In addition, Articles 100 and 101 of the WOG, in conjunction with Article 83 of the AVG, are imprecise and ambiguous, with the result that a party is unable - at the time when it adopts a certain course of conduct - to assess in advance in an appropriate manner the penal consequences of that conduct.[6]

It follows that Articles 100 and 101 of the WOG, in conjunction with Article 83 of the AVG, are contrary to the fundamental principles of substance/ legality and proportionality laid down in Articles 6 and 7 of the ECHR and Article 47 of the EU Charter. For these reasons, Articles 100 and 101 of the WOG, read in conjunction with Article 83 of the AVG, cannot provide an adequate legal basis for the Disputes Committee to impose a penalty on the Appellant.

The GBA clearly disagrees with IAB Europe’s interpretation and argues (in summary):

- The European legislator has deliberately opted for a wide margin for the penalty amounts, precisely because the AVG targets a wide variety of possible infringements;

- The Constitutional Court (judgment no. 25/2016 of 18 February 2016) itself states that a single, wide margin is not contrary to the principle of legality

- Article 83.2 AVG contains a whole series of criteria for adjusting the level of the administrative fine to the concrete circumstances of the case

- Full legality and proportionality control is carried out, if necessary, by the Market Court (adjudicating with full jurisdiction).

The Market Court rules:

In a digital environment, the possibility of imposing an administrative fine is a means of putting pressure on every controller to scrupulously comply with data protection rules. This makes the administrative fine an additional guarantee for citizens that data protection rules will, in principle, be respected. The Administrative fines provided for in Article 83 AVG are punitive in nature and must therefore, in principle, comply with the same principles as criminal sanctions. One of these principles is the principle of legality. This means that it must be clear to those concerned what conduct they should avoid, and therefore the circumstances in which an administrative sanction can be imposed must be defined in detail. This should also apply to criminal offences which, as in this case, are included in a European regulation.

Administrative fines, like all corrective measures, must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive. The AVG does not provide for specific amounts or ranges, but only for an upper limit or maximum amount. For this reason, Article 83(2) AVG also provides that the decision to impose a fine and, in such a case, to determine the amount thereof, is taken on the condition that a number of elements or criteria are met. These criteria can also play a role as mitigating or aggravating circumstance. In total, Article 83(2) AVG lists 10 criteria, supplemented by an open provision. In order to achieve a consistent approach to the imposition of administrative fines, Working Party 29 (now the EDPB) developed a common interpretation of these assessment criteria. This is included in the Guidelines on the application and setting of administrative fines. However, this is only an interpretation by supervisory representatives who cannot substitute the legislator.

In order to meet this (as pragmatically as possible), all charges deemed proven, as requested by the Market Court, were explicitly included by the Dispute Resolution Chamber in the sanction form that was submitted to IAB Europe on 11 October 2021 (document A.179). The violations of the AVG identified by the Dispute Resolution Chamber were summarised at p. 2-3 of the sanction form. IAB Europe could respond to the Sanction Form or request a reopening of the debates.

The plea as formulated by IAB Europe is unfounded.

FOURTH GRIEF: THE COURT OF FIRST INSTANCE HAS NOT DETERMINED THE ADMINISTRATIVE MONEY BASED ON THE CRITERIA OF ARTICLE 82.2 (note: read 83.2) AVG AND IS DISPROPORTIONALLY HIGH

IAB Europe submits that the Dispute Resolution Chamber did not take into account all relevant elements for the determination of the amount of the administrative fine and failed to explain how the interpretation of the different elements affects the amount of the fine. In addition, the Dispute Resolution Chamber also combines the fine with various other corrective measures, without explaining how these measures relate to each other or justify a higher or lower fine.

Furthermore, the Dispute Resolution Chamber has also failed to give clear reasons for the amount of the fine itself. For example, the Dispute Resolution Chamber does not adequately explain why it is not possible to impose a different, less severe fine, particularly in view of the fact that it intends to impose this fine in conjunction with other remedies.

Finally, IAB Europe submits that the administrative fine imposed is disproportionately high and that the Dispute Resolution Chamber could hardly have imposed the sanctions with a penalty payment, as the AVG makes no mention of such a possibility. IAB Europe submits that, consequently, neither it nor the Market Court can ascertain which elements were decisive for the imposition of the administrative fine and that, accordingly, the contested decision is vitiated by a lack of reasoning in that regard.

The GBA argues that:

- The Dispute Resolution Chamber explicitly stated the reasons why it had opted for an administrative fine (among other corrective measures)

- Proportionality of the fine was fully justified: each of the 11 criteria of Art. 83.2 AVG was examined individually

- These motives must be read in conjunction

- There is no "negative obligation to state reasons" on the Disputes Chamber

- The EDPB guidelines state that the "precise impact of each criterion should not be quantified individually".

- Explicit account was taken of financial organisation & capacity

- Periodic penalty payments are possible pursuant to Art. 58.6 AVG.

The Market Court considered: In the present case, IAB Europe has not demonstrated that the Dispute Resolution Chamber has imposed a sanction that is insufficiently reasoned and/or manifestly disproportionate.

It is clear from the contested decision, firstly, that the Dispute Resolution Chamber has deliberately opted for the imposition of an administrative fine, in addition to the other remedies referred to in recitals 536-537 of the contested decision.

Secondly, the contested decision contains a statement of reasons for the fine imposed by the Dispute Resolution Chamber. The fine is based on sound, sufficient and supportable grounds. The contested decision states the reasons for the proportionality of the administrative fine of EUR 250,000 imposed, expressly applying all the criteria set out in Article 83(2) of the AVG.

Third, in imposing the administrative fine, the Dispute Resolution Chamber also took into account IAB Europe’s financial organisational structure and ability to pay (recital 560 et seq. of the contested decision).

Therefore, it has imposed anything but the heaviest possible (monetary) fine of EUR 250,000, but a fraction of what is legally permissible.

The Dispute Resolution Chamber did indicate in recital 571 why a less severe, lower fine would not be appropriate - and this, in light of the express requirement of Art. 83.1 AVG that "any supervisory authority shall ensure that the administrative fines […] are in each case effective, proportionate and dissuasive".

Finally, IAB Europe’s argument[7] that the GBA ’wrongly’ conferred on itself the power to impose its sanctions with a penalty payment on the basis of Article 100(1)(12) of the WOG cannot be upheld, since the AVG ’does not mention the imposition of penalty payments’ and the GBA cannot therefore impose penalty payments ’on the basis of national legislation which has no legal basis in the AVG’.

No unlawfulness under national law can be attributed to the Litigation Chamber in this respect. Article 101, §1, 12° WOG provides that "the Litigation Chamber has the power to: […] 12° to impose periodic penalty payments."

The plea as formulated by IAB Europe is unfounded.

FIFTH GRIEVANCE: THE INTERNAL RULES OF THE DISPUTE SETTLEMENT CHAMBER INFRINGE THE PRINCIPLE OF THE FORMAL LEGALITY OF CRIMINAL PENALTIES, GUARANTEED BY ARTICLES 12 AND 14 OF THE CONSTITUTION, AS WELL AS THE RIGHT OF DEFENCE.

IAB Europe states:

Several elements of the GBA sanctioning procedure are not legally laid down in the WOG but in the so-called Rules of lnteme Order of 15 January 2019 (hereafter: "RIO"). More specifically, the RIO contains rules regarding both the composition (articles 43-44 RIO) and the organisation (articles 45-54 RIO) of the Dispute Resolution Chamber. The appellant must point out that these provisions do not contain outer aspects of secondary importance, but on the contrary concern essential elements of the proceedings before the GBA, such as the allocation of cases within the Dispute Chamber (article 43 RIO), the procedure to be followed in the absence of the chairman of the Dispute Chamber (article 44 RIO), the disclosure of the identity of the complainant (article 47 RIO) and the non-public nature of the hearing (article 53 RIO).[8]

In the contested decision, the Dispute Resolution Chamber argues that the elements in the RIO relating to sanctions are ’by no means essential elements for the imposition of fines’ but are ’elements of a secondary or organisational nature’ (§254). The appellant does not see how the disclosure of the identity of the complainant, the non-public nature of the hearing or the composition of the Dispute Resolution Chamber are other secondary or organisational rules. These rules are essential to the proceedings before the Dispute Resolution Chamber and must safeguard the Appellant’s rights of defence.

For example, Article 6.1 of the ECHR provides that the Appellant has the right to have his case heard by "an independent and impartial tribunal established by law". This implies not only that the establishment of the Dispute Resolution Chamber should have a legal basis, but also that the composition and organisation of the Chamber should be determined by law. A different reading of Article 6.1 of the ECHR would lead to a complete erosion of this guarantee.

Accordingly, the present proceedings are being conducted on the basis of procedural rules that are contrary to Article 12 of the Civil Code, Article 14 of the Civil Code and Article 6.1 of the ECHR and therefore lack any proper legal basis. For that reason, the claims against the Appellant must be dismissed.

The GBA argues (in summary) :

- Under Art. 6 of the ECHR, an administrative penalty procedure is permissible if an appeal with full jurisdiction is available before a court within the meaning of Art. 6 of the ECHR (in this case the Market Court).

- IAB Europe wrongly confuses the principle of legality of Article 6.1 of the ECHR with the formal legality principle of Articles 12 and 14 of the Constitution. These two legality principles are far from being identical. Art. 12 and 14 GW: an administrative sanction procedure is not of a criminal nature in the Belgian legal order and, at most, the law must provide for ’general conditions and modalities

- In any case, all the "essential elements" of the Litigation Chamber’s procedure were laid down by the legislature itself in the WOG

- Art. 52 AVG furthermore obliges the legislator to delegate (part of) the regulation of the procedure to the GBA in view of the required independence of the supervisor

The Market Court considers that the organisational elements of the RIO relied upon by IAB Europe do not count as ’essential elements’ in the light of those constitutional articles, especially when those provisions are read in the light of the Union law requirement of independence of supervisory authorities which must guarantee the fundamental right to data protection.

SIXTH PLEA IN LAW: THE APPOINTMENT OF THE MEMBERS OF THE DISPUTE RESOLUTION CHAMBER IS CONTRARY TO ARTICLE 53 OF THE AVG AND CONTRARY TO PUBLIC POLICY

IAB Europe argues that except for the publication of the vacancies in the Belgian Official Gazette, the WOG does not contain any substantive provisions on the modalities of the appointment procedure of the members of the GBA, including the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber. It is not clarified how the hearing of the candidates should proceed, nor does the WOG require a written report of the hearing. Moreover, the nomination takes place on the basis of a secret ballot and there are no guarantees as to the adequacy of the information on the candidates provided to the members of the Chamber of Representatives.

For this reason, the appointment procedure is clearly neither objective nor transparent - and the appointment of the members of the GBA, including the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber, thus fails to meet the requirements of Article 53 AVG, which stipulates that the ’supervisory authorities shall be appointed in accordance with a transparent procedure’.[9]

Since the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber were not appointed in accordance with the requirements of Section 53 AVG, they cannot make a legally valid decision in relation to the Appellant. For these reasons, too, the claims against the Appellant should be dismissed.

In the contested decision, the Dispute Resolution Chamber argues that ’any impediments to the appointment procedure of the members of the GBA cannot form part of these proceedings and the parties cannot invoke a procedural interest to question the appointment procedure’. be interest to question the appointment procedure." The fact that the rules on the appointment procedure of the eden of the GBA are not clarified in the WOG, are not objective nor transparent, the Dispute Resolution Chamber sees as a mere "imperfection". However, the Appellant regards this as a serious breach of Article 53 of the AVG. It was in the Appellant’s interest that this issue be raised, as it was the same members who had taken a decision with far-reaching financial and operational consequences. If it emerges that these members were not appointed in accordance with a proper procedure, these members cannot take a valid decision either.

In summary, the GBA states the following:

- The Market Court has no jurisdiction to rule on the validity of the appointments of the House of Representatives, pursuant to section 108 of the WOG (cf. judgment 8 June 2022 MH).

- Article 159 of the Constitution is not applicable either:

- Administrative legal acts of legislative assemblies are not covered by Art. 159 of the Constitution

- Moreover, appointment decisions are not regulatory ’acts or regulations’.

The Market Court considers that its ability to apply Article 159 of the Constitution is circumscribed by the special jurisdiction which it enjoys pursuant to Article 108 of the WOG, and that jurisdiction does not include - as already stated above - the ability to assess the validity of the decisions of the House of Representatives implementing Article 39 of the WOG. Contrary to the contested decision itself, the appointments of the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber by the House of Representatives in respect of IAB Europe do not constitute ’a legally binding act relating to him’. decision" within the meaning of Article 78.1 AVG, which is subject to appeal before the Market Court.

It is only the House of Representatives that can apply Article 45 of the WOG and has done so recently:

Art. 45. § 1. The House of Representatives can only relieve a member of the management committee, a member of the knowledge centre and a member of the chamber of disputes of his mandate if he has been found guilty of serious misconduct or does not meet the requirements for the performance of his duties.

The Dispute Resolution Chamber of the GBA acts as an administrative body (and not as a judicial body). A possible (hypothetical) irregularity of the appointment of the members of the Dispute Resolution Chamber - and/or the possible adoption thereof - cannot affect the legality of the decisions taken by them. After all, the legality of the actions of officials whose appointment is annulled (or would be considered invalid) cannot be questioned on the basis of the unlawfulness of their appointment for the sake of the continuity of the public service.

The plea is unfounded.

SEVENTH GROUND OF APPEAL: THE WAY IN WHICH THE ARBITRATION BOARD HAS DEALT WITH THE PROCEEDINGS IS CONTRARY TO ITS DUTIES AND POWERS AS DATA PROTECTION AUTHORITY UNDER THE WOG AND THE AVG , VIOLATES THE APPELLANT’S RIGHTS OF DEFENCE AND DISREGARDS THE PRINCIPLE OF DUE CARE AS A PRINCIPLE OF SOUND ADMINISTRATION IN CONJUNCTION WITH THE DUTY TO STATE REASONS SET OUT IN THE EIGHTH GROUND OF COMPLAINT

IAB Europe states:

The manner in which the GBA has dealt with these proceedings against the Appellant has resulted in several breaches of the provisions governing its duties and powers as the GBA. In particular, the GBA infringed Article 57(1)(a) and (f) AVG in conjunction with Article 51(1) AVG, Section 58(1) AVG and Section 94 WOG. By violating these procedural requirements, the GBA oak disregarded the principle of due care and the Appellant’s rights of defence.

And

The Dispute Resolution Chamber therefore has three obligations arising from Article 57(1)(f) AVG. First, it must deal with complaints referred to it by data subjects. Secondly, it must, as far as is appropriate, investigate the content of the complaints. Finally, the Dispute Resolution Chamber must inform the complainant of the progress and outcome of the investigation within a reasonable period of time. In this case, the GBA failed to comply with the first two obligations.

The GBA refers to the contested decision which already provides an answer to this grievance in recital 265 et seq. It also considers that IAB Europe reads principles into the AVG & WOG that do not appear in it. It posits that:

- The investigation of the Inspectorate is situated in the "preliminary procedure" (subsection 2, art. 96 WOG): after this, the intervention of the Inspectorate ends legally (art. 96, §1 &2 WOG).

- The preliminary procedure is followed by the adversarial procedure between the parties (art. 98- 99 WOG)

- Parties (including complainants) may "annex to the file any documents they consider useful".

- Neither the AVG nor the WOG can be interpreted as meaning that the Dispute Resolution Chamber may not take ’new elements’ into account, provided that the parties object.

- Principle of due care does not lead to a different conclusion ’contra legem’: only requires a careful examination by the Dispute Chamber, not a ’double examination’ or ’second opinion’ by the Inspectorate

- Nor does Article 57(1)(f) AVG lead to a different conclusion: AVG does not address the relationship between the Dispute Resolution Chamber and the Inspectorate + the passage "to the extent appropriate" only relates to the power to dismiss the proceedings of the Dispute Resolution Chamber

- In any event, IAB Europe’s complaint ’in fact’ fails: IAB Europe does not give a single concrete example of a ’new’ fact that was incomprehensible and about which no contradiction could be made without additional investigation by the Inspectorate.

The Market Court considers the following:

The following conclusions may be drawn from the contested decision with regard to: (a) the existence of cross-border processing; (b) the reasons for which the GBA considers itself to be the leading supervisory authority; (c) the information provided in that regard to the IAB and its rights of defence in that regard:

1. In the course of 2019, a series of complaints were lodged against Interactive Advertising Bureau Europe (hereinafter IAB Europe), for breach of various provisions of the AVG for large-scale processing of personal data. The complaints concerned, in particular, the principles of lawfulness, fairness, transparency, performance, minimisation, storage restriction and security, as well as accountability.

2. Nine identical or very similar complaints were lodged, four directly with the Data Protection Authority (hereinafter ’DPA’) and five via the IMI system with supervisory authorities in other EU countries.

3. The Inspectorate also carried out investigations on its own initiative, pursuant to Article 63(6) of the WOG. Because the complaints relate to the same subject matter and are directed against the same party (IAB Europe), and on the basis of the principles of proportionality and necessity in the conduct of the investigation (Article 64 of the WOG), the Inspectorate merged the above files into one case under file number DOS-2019-01377.

4. The complainants have agreed to this amalgamation, as well as to the request by the Dispute Chamber to combine their claims and submit them as a joint package, in the interests of economy and efficient proceedings.

5. In this international case, four complainants, including the NGO Ligue des Droits Humains, are domiciled in Belgium, one in Ireland, four in different EU states, represented by the Polish-based NGO Panoptykon, and one complainant is represented by the Dutch-based NGO Bits of Freedom.

6. Under Article 4(I) of the WOG, the Data Protection Authority is responsible for monitoring the data protection principles contained in the AVG and in other laws containing provisions on the protection of the processing of personal data.

7. Pursuant to Article 32 of the WOG, the Dispute Resolution Chamber is the administrative dispute resolution body of the CFI.

8. Pursuant to Articles 51 ff. AVG and Article 4 § 1 of the WOG, it is the task of the Litigation Chamber, as the administrative disputes body of the CFI, to exercise ejctive control over the application of the AVG and to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons with regard to the processing of their personal data and to facilitate the free flow of personal data within the European Union. These tasks are further explained in the Strategic Plan and the Management Plans of the GEA, drawn up pursuant to Article 17, 2°, of the WOG.

9. With regard to the one-stop- shop mechanism, Article 56 AVG further provides: "Notwithstanding Article 55, the supervisory authority of the principal or sole establishment of the controller or processor competent to act as a leading supervisory authority for the cross-border processing carried out by that controller or processor, in accordance with the procedure set out in Article 60.

10. Article 4.23 AVG clarifies the notion of cross-border processing in the following terms: ’(a) processing of personal data in the context of the activities of establishments in more than one Member State of a controller or of a processor established in the Union; or (b) processing of personal data in the context of the activities of an establishment of a controller or of a processor established in the Union, which substantially affects or is likely to affect data subjects in more than one Member State; ’.

11. The defendant has its sole seat in Belgium, but its activities have a significant impact on stakeholders in several Member States, including the complainants in Ireland, Poland and the Netherlands, as well as in Belgium. The Dispute Resolution Chamber bases its jurisdiction on a combined reading of Articles 56 and 4(23)(b) of the AVG. The GBA was seized by the Polish, Dutch and Irish data protection authorities following a complaint made to them by the complainants, in accordance with Article 77.1 of the AVG. It declares that it is the leading supervisory authority (Article 60 AVG).

Apart from the very brief statement that ’the GBA claims to be the leading supervisory authority’, the disputed decision does not contain any other reasoning concerning the facts or legal grounds on the basis of which the Disputes Chamber found that cross-border processing took place, nor does it make it possible to deduce why the GBA considers itself to be the leading supervisory authority. It is regrettable that the Dispute Resolution Chamber does not explain the application of the rules relating to the one-stop shop, as these rules are not always easy to apply in practice.

Nor can it be deduced from the contested decision itself whether IAB Europe, as the alleged controller, was informed in advance and made aware of the existence of cross-border processing, of the role of the GBA as the leading supervisory authority and of the cooperation with other authorities pursuant to Article 60 of the AVG. A review of the administrative file shows that this was indeed done by letter of 9 October 2020, as required by Article 95 WOG (documents A077 and A078). However, that letter only concerned the original complaints and not the later allegations and complaints added by the complainants (see below).